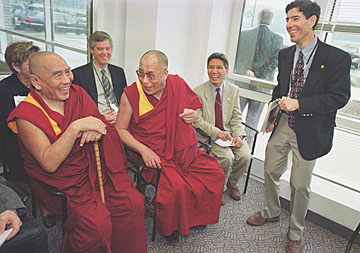

Professor Davidson (standing) with

His Holiness the Dalai Lama and Geshe Sopa

Interview with Professor Richie Davidson

By Susan Gemmill

On the last gray day of January 2002, I had the pleasure of interviewing the engaging Professor Richie Davidson. Davidson is a UW Professor of Psychology and the Director of the W.M. Keck Laboratory for the Functional Brain Imaging and Behavior at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Over the past decade, Richie has been pursuing some remarkable research regarding the physiological effects of meditation, specifically upon the brain and the emotions. In May of 2001, His Holiness the Dalai Lama returned to Madison to tour the lab and catch up on the latest research techniques. The following is an excerpt of our conversation:

When did you know that you wanted to devote yourself to the study of the brain?

RD: I volunteered for a sleep study in high school. I knew at that time that my life would have something to do with the mind. I was also very early on, influenced by intuition and what I saw as a set of methods that were potentially available to all people; methods that might facilitate the transformation of certain kinds of mental qualities that would be beneficial. That was something that was very attractive to me.

My own experiences at that time were quite limited but were sufficient to convince me that the traditional account of our makeup and repertoire of skills and competencies was limited unnecessarily; that the interaction with Buddhist traditions was important in helping us call into question those limitations and help us expand our domain of what is possible. That vision is something that has been compelling and attractive to me.

I also feel blessed by my interactions with H.H. the Dalai Lama. The past decade has helped me to solidify my commitment to these areas. I’ve always been committed to them personally, but they’ve sort of been on the scientific back burner for many, many years. Over the past several years, I’ve sort of come out into the open with this stuff in a much more public way and that’s felt appropriate and good. I think the time is right so I’m very excited and optimistic about these activities.

As a graduate student at Harvard I was interested in meditation. In fact, when I was an undergraduate student I was interested in meditation. There was a lot of activity around Cambridge in the early 1970s. Ram Das was spending a lot of time there and I spent many years hanging out with him. He taught an informal class on Tuesday evenings that was my alternative education, a compliment to all the things I was learning.

After two years in graduate school I spent three months in India at my first serious meditation retreat. That was very important to my opening up. It exposed me to the possibilities of these kinds of practices. I’ve been involved in them ever since but they haven’t been the central stage of my scientific research. I did publish a number of articles as a graduate student and did some research in the area but it was clear that the tools available to us at that time were not particularly refined. The subtleties of meditation practice were not particularly well captured by those tools. It’s only recently that we’ve begun to focus on these questions in some of our science even though very early on, I was interested in these things. The reason for the return to a formal scientific study of meditation is, in part, because the tools we have today are so much more powerful.

Will you elaborate on the tools currently in use?

RD: They are completely non-invasive which is one of the virtues of this type of research. Nothing is injected into the brain there is no exposure to unwanted side effects. Each device is completely safe which allows us to image blood flow without concern. The geodesic sensor net contains 256 electrodes and is worn on the head like a lightweight helmet. The fMRI is a tunnel in which the test subject lies completely still. It captures real-time responses to emotional stimuli in various regions of the brain. It’s a functional MRI so you are working while you’re in there. It’s noisy but we give you earplugs. The PET scanner detects metabolically active areas of the brain by picking up signals from a radioactive tracer injected into the subject before the procedure.

Have you worn the sensor net, gone through the PET and fMri?

I never have a person do anything that I haven’t done first.

Are there any sensations, tingling, sensations?

No. The net is very comfortable, after 5-10 minutes you don’t even notice that it’s on. The fMRI scanner is different, you are deep within the bore of the scanner and it makes a lot of noise. And you have to lie extremely still, those measures are very intolerant of movement, so you have to lie very, very still. But I kind of enjoy going in there. I’ve actually been in there for more that 6 hours completely at ease. We wouldn’t do that to an ordinary person.

When did you first suspect the connection between emotions and disease?

RD: I think since the time I started thinking about these issues seriously, I was always convinced that there was a link. What I think is different now is rather than doing research to confirm that there’s a link, we take that link as a starting point and the work that we’re doing is to focus more on the mechanisms which account for the link not so much is there a link.

I think that most people in this area today will accept the conclusion that there is some link for at least certain kinds of disease, not for all diseases, but for certain kinds of diseases. And the question is why is there that link, what accounts for that link, how can we understand how that connection comes about and why is it the case that certain diseases may be more susceptible to emotional imbalances whereas other diseases are not? I think that is a piece of very telling information and helps us better understand what these mechanisms are.

Can you verbally pinpoint the location of the amygdala?

RD: Sure. On the sides of our brains here are the temporal lobes and the temporal lobes come down and fold in. Imagine them coming out and folding in at the medial portion of the temporal lobe just right about at the temple. Just right in front of the ears on each side of the brain is an almond shape structure that is about 1 and _ centimeters in diameter and that is the amygdala. There’s a lot of research that’s been done on the amygdala and it’s clear that it has a connection to the emotions, especially negative emotions, but not it seems specifically connected to negative emotions even though it maybe preferentially.

The best way to describe it is when something potentially dangerous occurs near us and we need to figure out what it is. We need to investigate it so we don’t screw ourselves up and pursue an adaptive course of action. So if you are walking along a ledge and it is very dangerous, your ability to detect that danger is in part due to your amygdala. The amygdala cares about things which are significant for our survival and it will then recruit other brain regions to further investigate and view the stimulus or situation to figure out whether it really is dangerous or whether it is safe then the amygdala is no longer needed. It tends to be short acting and involved in the initial stages of emotional learning.

In patients with certain kinds of psychiatric disorders the amygdala gives fire to things that in normal individuals the amygdala wouldn’t care about. So for example, in patients with social phobia, these are the kind of patients who particularly scared of public speaking it’s very debilitating. Many of these people are really frightened of being in groups in general and constrain their occupational ad vocational activities because they have these very severe fears. In those individuals if you just present to them neutral faces of strangers, people they don’t know, that activates the amygdala. In normal individuals that kind of stimulus has no effect on the amygdala. So, there are clear abnormalities of the amygdala in certain psychological disorders. That’s something that we study.

I should say that most of our research is not done on meditation and the bread and butter of what I do, so to speak is focused on trying to understand what’s different about the brains of the patients who suffer and various kinds of debilitating psychiatric illnesses like depression, anxiety. So kids who are predisposed to those kinds of disorders in the hopes that we can develop more effective treatments and eliminate that kind of suffering.

How was the amygdala first pinpointed? How was it discovered that this is the part of the brain that does all that it does?

RD: It was discovered in animal research. There’s a lot of foundation in animal studies that provides clues as to how this works in people but then there’s also a few individuals who have this very weird neurological disorder, it’s initially a skin disorder that initially presents as a dermatological disorder and in a very, very small percentage of the cases the disorder also involves mineral deposits in the brain and for reasons no one yet understands these mineral deposits are very selective. There are a couple of these patients whose amygdalas have been destroyed but everything else about their brain is fine. It’s exceedingly rare but there are a couple of cases that have been reported in the world literature and these are interesting people. They do appear to have some very specific deficits in the processing of fear. These are people when recent research has shown they can identify facial expressions of emotion just fine with the exception of the facial expression of fear. It’s amazingly bizarre kind of disorder.

What type of emotional stimuli do you show your test subjects?

RD: We’ve used photo images, filmstrips, pictures, sounds and we’ve been working with tastes. We also often rely on people’s life histories. We have people think about then write about the most intense positive and negative emotional events of their lives; particularly older individuals who have been around for some time. That can be a very powerful procedure to use and analyze.

And then we are interested specifically in positive emotions and trying to figure out how we can begin to study something like compassion, which is not easy. And so one of the things that we do, we just finished this crazy study: we brought in women who had just given birth to their first babies. These are women with 3 month-old babies. We brought the women and their babies into the lab and took pictures of the babies. Then we brought the mothers back for a second session and we put them in the fMRI scanner and we showed them pictures of their own babies versus pictures of other mother’s babies that they had no previous experience with. We reason that there is a special emotional quality of a mother with her first born so we are using that as a method to try and evoke a certain kind of emotion and study the change in the brain. Those are some to the things we are doing.

Do you see Psychologists/Psychologists using meditation as a means to treat their patients?

RD: Absolutely. Meditation is not going to be good for all patients with emotional disorders and it may even be bad for certain types of patients. It’s clear that it will be helpful as an adjunct. There is a British scientist who is very well known, John Teasdale, a depression researcher. What John has actually demonstrated is that mindfulness meditation can significantly improve a depressed patient’s ability to prevent relapse. So it’s not so much effective in treating initial depression but once the depression has subsided they can begin to practice the meditation. They can actually significantly minimize relapse. So that’s one example where meditation may be very effective in certain kinds of cases and in particular kinds of circumstances. A lot of psychiatrists are getting very interested so I think that’s a really good sign. Many psychiatrists that I know are genuinely interested in the application of meditation and are referring their patients to meditation groups as an adjunct to whatever else they are doing for therapy.

Have you studied the effects of various kinds of meditation practices?

RD: We did one formal study relatively recently with Jon Kabat-Zinn. We were looking at meditation based on the mindfulness tradition of Theravada Vipassana practice. We have an ongoing project bringing in adepts who are extraordinarily accomplished. There aren’t that many of those people on the planet as I’m sure you’re well aware. It’s not something we can put an ad in the Isthmus and look for subjects so it’s kind of necessarily slow going in terms of collecting data.

We tested one person who was here with His Holiness in May, a French Buddhist monk, Matieu Ricard, who has done a number of prolonged retreats, more than 3 years, a rough criterion for long-term practice is 10,000 hours, and Matieu has practiced way above that. We looked at a number of different meditation practices, some Meta practice, guru devotional practice, and we looked at the differences in the brain during these various practices. We now have three additional people that are scheduled to visit within the next eight months.

In this case, all the practices are in the Tibetan tradition for a variety of reasons but largely because we have a very good relationship with and access to extraordinarily kind cooperation from the Tibetans. Our goal is that over the next couple of years to complete ten of these studies.

How did your relationship with the Dalai Lama first come about?

RD: Well, it’s really more that I felt chosen by him. I was asked by his office to participate in a scientific expedition to study the brain function and mental activity of accomplished Tibetan yogis. His Holiness initially contacted me asking if I’d be interested in this kind of venture. He had heard about my work form others who had interacted with him. So, the first time I met him was in 1992. I went to India explicitly to meet His Holiness and to talk to him about this project. We organized a small team, three scientists and two translators, flew over and met with His Holiness. We spent several weeks in Dharamsala interviewing yogis who were potential participants in this research. His Holiness provided access to these individuals so that was sort of the beginning.

That was quite a beginning.

RD:(Laughing) Yes, it was quite a beginning.

What has been the most profound insight you have gained from your association with His Holiness? How has he inspired you?

RD:I guess the most profound insight for me is a direct evidence of being in the Dalai Lama’s presence. The extraordinary power of compassion and as a consequence of that the extraordinary capability of human transformation. Every time I’m in his presence I am deeply affected, it just happens. The very first time I went to meet him I remember being extremely anxious. To meet with the Dalai Lama you have to go through a lot of security and I had all this anxiety. Fifteen seconds of being in his presence my anxiety was completely gone. The feeling was a deep, deep sense of security, just feeling extraordinarily calm. The transition feels mind-boggling, never have I had that kind of transition where I might be anxious before seeing someone then to have it so completely transformed and in such a profound and intense way.

And one of the really cool things regarding the Dalai Lama is that he’s meeting with all these incredibly famous scientists. When they visit with him then go back to what they do they are very different people. That is amazing.

Do you have a fond memory that occurred between the two of you that you are willing to share?

RD: You know that I’m a student of emotion, that’s what I study and there are a couple of things I’ll say about that. One is that His Holiness, to me, exhibits a dynamic range of emotions. What I mean by dynamic range is in any given interaction there is an extraordinary pallet of emotion that is on display. He can go from being dead serious and stern in a certain way in an interaction then instantaneously just crack up.

That’s part two of this: his transitions are so sharp and fast. I’m sure everyone has observed an infant who may have fallen down and is crying, you tickle the child and he starts laughing instantaneously. As adults we seem to lose that quality, that ability to sharply transform our emotions. His Holiness exhibits these qualities. That’s amazing.

Another specific anecdote is, when His Holiness talks to you he might touch your ear or chin. He’s the only one on the planet who can get away with it. I introduced him to my wife for the first time in May and he held each of us under our chin and brought us very close together, close to him, and he looked from one to the other then declared, “Same nose!” So that was a great and insightful memory of His Holiness.

You are a member of the International Committee of Scientists for Tibet. The Committee sent a moving letter to President Jiang Zemin and Prime Minister Zhu Rongji of the PRC voicing concern over “the dismantling of the culture of Tibet and especially its heritage of Buddhism.” In the letter the committee recognizes the contributions to the study of the mind made over many centuries by Tibetan Buddhist Culture. What is the Committee’s greatest goal? What is it you hope to achieve by coming together as an international unit?

Our goal is to bring the stature of the International scientific community to bear on the leadership of China to express to them the fact that the worlds’ leaders in the behavioral and biological sciences believe that there is something precious and extremely worthwhile in the Tibetan culture that should be preserved. And quite a few of the signatories of that letter are Nobel Laureates. We are hoping to add our voices and bring the weight of that community to bear, to exert some political pressure to try to address the crisis that’s occurring.

You’ve met Geshe Sopa many times. Have you a fond memory of him as well?

RD: Just seeing him interact with His Holiness. I’d love to spend more time with him; I honestly don’t know him very well. I do go to Deer Park occasionally. I’d like to go more often

You’ve given me a lot of information. Is there anything you’d like to add?

That’s good. I don’t know if you’ve seen this (he gets up and goes to another table, grabs a book he’s written) Visions of Compassion.

I will have to read this.

RD: Please do, then tell me what you think.

I appreciate your time.

RD: It was fun.

| Home | Geshe Sopa | Deer Park | New Temple | What's New |

| Past Events | Photo Gallery |